Peter Thiel, Rene Girard, and Vance's Moral Conundrum

Scapegoating and sacrifice in Contemporary America

Our Vice President misinterpreted a social scientist and, as a result, converted to Catholicism.

If you read JD Vance’s 2020 essay (“How I Joined the Resistance”) about his conversion to Catholicism, you’ll learn that his real moment of spiritual transition from atheist to Catholic oddly came during a 2011 talk that Peter Thiel gave at Yale Law School.

How?

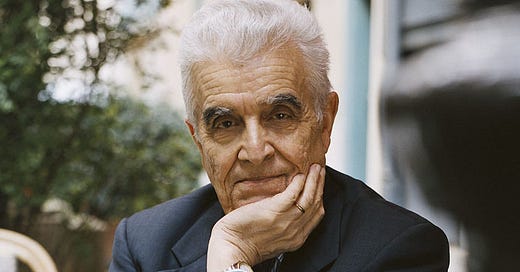

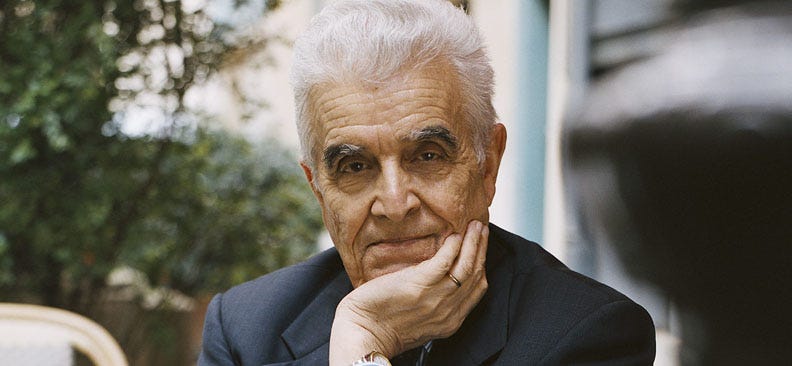

Weird as that is to say, this talk launched our VP into a study of the world of one of Thiel’s mentors, the French philosopher René Girard. I’m basically of the opinion that it was a misreading of Girard that led Vance to Catholicism, and it is this misreading that has put him in an irresolvable moral spot ever since. Here’s what I mean.

The main idea that René Girard is famous for is his “theory of memetic desire,” which is sort of a mechanistic account of how civilization emerged. The theory goes like this:

Memetic desire: Most of what we want (desire) is just what other people want. As Vance writes in his essay, “…that we tend to compete over the things that other people want—spoke directly to some of the pressures I experienced at Yale.”

Memetic rivalry: The fact of memetic desire leads, naturally, to memetic violence, people fighting for the same things, which are scarce because everyone wants the same shit. As more people imitate each other, the conflict escalates, spreading through the group. Writing about his time at Yale Law School, Vance writes that “we fought over jobs we didn’t actually want while pretending we didn’t fight for them at all.”

The scapegoat mechanism: To resolve this dynamic as it swells, human societies unconsciously select a scapegoat, an individual or group blamed for the crisis. Killing or expelling the scapegoat restores peace temporarily and becomes mythologized as sacred or divine.

For Girard and Vance, this cycle was basically all of human society forever until Christianity broke the cycle. Literally, the whole point of Christianity is to break this cycle, to say that actually that scapegoat y’all selected to kill (Jesus) is actually, like, a pretty good guy! What the fuck are we doing?

The Gospels expose the innocence of the victim (Jesus) and thereby unravel this sacrificial logic of human culture (the scapegoat mechanism). Here I should say explicitly that for Girard, a major goal must be to escape the scapegoat mechanism entirely. But this is where Vance falls into the oh-so-American trap I like to call “the reverse scapegoat.” In his Christian conversion essay, he writes that

To Girard, the Christian story contains a crucial difference—a difference that reveals something “hidden since the foundation of the world.” In the Christian telling, the ultimate scapegoat has not wronged the civilization; the civilization has wronged him. The victim of the madness of crowds is, as Christ was, infinitely powerful—able to prevent his own murder—and perfectly innocent—undeserving of the rage and violence of the crowd.

Rather than escaping the scapegoat mechanism, this typically American logic simply reverses it: society becomes the scapegoat for real and imagined individual failures.

This “reverse-scapegoat mechanism” serves as the structure for all of Ayn Rand's characters, archetypes of what Corey Robin has called the "brilliant individual wronged by the masses." All of Rand's protagonists, such as Howard Roark and John Galt, embody the "demigod-creator" in conflict not directly with the masses but with intermediaries—intellectuals, bureaucrats, and middlemen—who obstruct the creator's connection to the masses.

Hilariously, at the same time Ayn Rand was railing against Christianity as “the best kindergarten of communism,” she was reproducing the tradition’s core myth.

This character type was enormously appealing to free-market Americans seeking to justify liberal individualism against the bureaucratic mediocrity of Soviet Communism. It is also essentially the role that Vance imagines himself playing within the same mediocrity of Middletown, Ohio, then The Ohio State University, then Yale Law School, and then the White House itself.

It is also, for what it’s worth, a problem on the left that robs marginalized populations of their own agency to better their lot. People of all colors, classes, genders, and religious faiths are not purely victims of some “structural” problem in society, whether racism, sexism, or late-stage capitalism.

Thus, the Christian logic, the tyranny of the structure (or idiotic masses), and the reverse-scapegoat are the characteristic frames for most of our mainstream politics today, the primary goal of which is to justify each of our own everyday sense of inadequacy and failure and meaninglessness. This dynamic provides a wellspring for social media addiction, which creates a market for advertising and digital sales atop which our entire modern economy is built. Girard’s original insight, that we basically desire what others desire (memetic desire), is further confirmed by the unimpeachable material success of our modern digital world, which commodifies our attention and sells our few precious moments on this beautiful planet to the highest bidder—for me, usually “cool t-shirt companies.”

This is an aside, but mark this down: I think Vance will end up a Democrat by the end of his political career. Add it to your bingo card.

Okay, but the whole point of Girard’s theory was to escape the scapegoat mechanism entirely, not just reverse it. Vance believes that Christ is innocent and society is guilty. The victim unmasks civilization’s violence. Now we must see the truth and reject the crowd.

At first glance, this seems aligned with Girard—but it subtly reactivates the scapegoat logic, just inverted: now it is “society,” “the deep state,” or “woke people” that becomes the villain, the accused, the condemned. We—the ones who “see through it”—are the righteous few. This turns what should be a critique of universal human participation in violence, wokeness, and late-stage capitalism into a new, purifying accusation. The system becomes the demon we cast out to explain everything.

But this brings us back to the irresolvable problem of sociology itself: structure versus agency. The truth is twofold: individuals are entangled in social structures that are produced by individuals. The scapegoat mechanism alternates between both causal directions. Vance thinks he’s escaping the scapegoat mechanism when what he is really doing is just advocating for the other side of the same coin of sacrifice.

For Girard, the only way out of the scapegoating mechanism is forgiveness, repentance, and a refusal to accuse—even when one is “right.” There is actually no other way. This is what our current vice president, at least as far as I can tell, does not understand. It is what, I imagine, both Popes and all the Cardinals he brags about talking to push him toward—or, at least, I hope.