I don’t even remember how I stumbled upon this stuff.

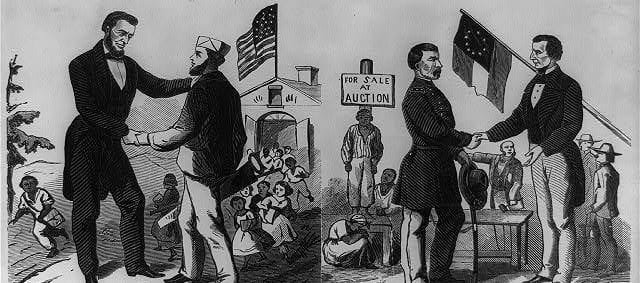

The earliest reference to sociology in the United States was in the slaveholding South. That history has been mostly forgotten—maybe for the better. But buried in it is something eerily relevant to today’s political landscape.

Sociology for the South, Or the Failure of a Free Society (1854) is a pro-slavery manifesto (shocker) by George Fitzhugh. But it’s also an acid trip into another era of political thought.

In short, Fitzhugh thinks slavery and socialism are synonyms—and that both are desirable alternatives to free-market capitalism. He sees two competing visions for society: one based on competition and liberty, and another based on protection and hierarchy. He’s pro-the-second one, which includes both slavery and socialism.

Liberty, Free Trade, and the Globe

The first of these two is what he calls “the philosophy of free trade and universal liberty,” with Adam Smith as the central figure and the Northern US and Europe as the centers of power. In this philosophy of society, the interests of the strong, wealthy, and wise reign supreme. In this kind of society, the dignity of the working class is not guaranteed but earned. Central to this philosophy is the competition between poor and poor and between poor and rich. Because of this, in these kinds of societies, “the poor can neither love nor respect the rich, who, instead of aiding and protecting them, are endeavoring to cheapen their labor and take away their means of subsistence.” In these free societies, the rich people with capital destroy labor, the rich inevitably come to resent themselves, and “good men and bad men have the same end in view: self-promotion, self-evaluation.” With no protections for the poor and destitute, “pauperism” proliferates.

Slavery, Socialism, and the Region

Now, the second of these two philosophies of society, and the one the pro-slavery Fitzhugh is in favor of, is socialism (the fuck?). The philosophy of a socialist society is to protect the weak, poor, and ignorant. In this kind of society, laws are passed to restrict the “destructive competitive propensity” of the free market. He pushes back against the Hobbesian notion that free marketers push that “a state of nature is a state of war,” because men are naturally associative and peaceful. In this kind of society, it is the sole purpose of government to protect the weak from the strong and from themselves. For Fitzhugh, “it is fortunate for man that he loses his love of liberty just as fast as he becomes moral and intellectual.” Society must not be a war between rich and poor, powerful and weak, intelligent and dumb—in free society we “see the war, but no the improvement.” He writes that after all the convolutions of the French Revolution, France returned to make Louis Napolean an Emperor. Fitzhugh writes that “he is a socialist, and socialism is the new fashionable name for slavery.”

This is the point in the book: “Somewhere around Barstow on the edge of the desert when the drugs began to take hold.” For Fitzhugh, there is actually no categorical difference between slavery and socialism, and he is an advocate of both. They are two visions for society where it is the role of the government to protect the weak from the powerful. He writes that only slavery can bring about peace and respect between rich and poor, master and slave. He writes that while promoting liberty, the intellectual classes of the North and Europe are “unconsciously marching” toward slavery and away from liberty.

Choosing The Path

Of these “two philosophies,” Fitzhugh believes that you cannot have it both ways (i.e., both universal liberty and universal protection):

The working class and their advocates must decide on which of the two positions they will take their stand: whether they will be cared for as dependents and inferiors, or whether, by wisdom, self-control, frugality, and toil, they will fight their independent way to dignity and wellbeing; whether they will step back to a stationary and degraded past or strive onward to the assertion of their free humanity? But it is not given to them, any more than to other classes, to combine inconsistent advantages: they cannot unite the safety of being in leading strings with the liberty of being without them; the right of acting for themselves with the right to be saved from the consequences of their actions; they must not whine because the higher classes do not aid them and refuse to let these classes direct them; they must not insist on the duty of government to provide for them and deny the authority of government to control them; they must not denounce laissez-faire and denounce a paternal depotism likewise (62).

I think for a lot of my life I could not understand how “Dixiecrats” ever existed. Well, this was my answer. The funny thing he says about who supports which of these two kinds of societies is counterintuative. Even back in 1854, he notes something that will resonate today: that elites in the North promote socialism, even if their society is the bastion of liberty, whereas elites in the South promote free marketism, even if their society is the bastion of slavery.

The reason for this is that, on the one hand, Northerners have direct experience with the actual evils of universal liberty and free competition and desire to get rid of them. “They propose a remedy, which is in fact slavery (socialism); but they are wholly unconscious of what they are doing because, never having lived in the midst of slavery, they know not what slavery is.”

On the other hand, Southerners have little direct experience with universal liberty and competition, and some come to believe that “free competition is an unmixed good.” Southerners, with little real experience with the extremes of liberty, “look upon all socialists and radical reformers [in the North] as madmen or knaves. [The South] is as ignorant of free society as [the North] is of slavery.”

The Return of Dixiecratic Paternalism

Why does this matter now? Because there is some subtle dimension of Fitzhugh’s logic creeping back.

Look at JD Vance, Adrian Vermeule, and Curtis Yarvin—all big names in what gets called the “post-liberal right.” They aren’t libertarians. They reject free-market ideology. And they all think the government should forcefully shape society for the common good. Vance pushes a Catholic-inspired “Daddystate” where the government molds culture like a father disciplines his kids—I mean, look at how intentional he is about having his children in every photo-op. Vance once introduced a bill in the Senate with Elizabeth Warren to reign in the power of credit card companies.

Meanwhile, Vermeule’s Common Good Constitutionalism says law shouldn’t just protect individual rights—it should enforce morality. Yarvin wants a monarch-like CEO running the country, where efficiency and authority matter more than democracy. He and other “Theobros” use the term “monarchy” a lot only because it triggers attention in our media ecosystem from those who rightly believe that the United States was founded in direct ideological opposition to monarchy.

None of them really believe in “letting the market decide” like the Kochs of an era past. But where the rubber hits the road with these Reaction Bros is whether they believe that the role of government is to protect the weak or to promote the powerful. They believe in order, protection, and strong rule. But for whom? This is the question that ultimately matters.

I’ve heard people call these guys monarchists, theocrats, paleoconservatives, and proto-fascists. But no one calls them Dixiecrats.

Maybe they should. Or, Yankublican. Ugh, no.

Anyway, not because of segregation—that’s not the parallel. But in their relationship to labor, state power, and economic paternalism? The similarity is real.

While perhaps not a literal Dixiecrat, Vance feels like an ideological heir to Dixiecrat labor paternalism, along with all its hypocrisy. He even comes from the region of the country (upper Ohio River Basin) where this kind of Conservative Democratism lived on the longest (e.g., West Virginia).

This purely American politics has a complex history in relation to everything from tariffs to localism. The Dixiecrat coalition existed from 1865 through 1964, when Senator Strom Thurmond switched to the Republican Party. Notably, this coalition emerged just a decade after Fitzhugh’s Sociology for the South (1864)—and, of course, after the Civil War.

I think the thing that Fitzhugh reminds me of is that not every critic of the rapacious nature of free market capitalism is a Marxist. I think this is something that today, especially within the academy, we tend to forget. The haunting reality of the history of American policymaking is that the only reason the New Deal was passed was because it was supported by the Dixiecrats, and thus at the expense of Black workers. This deal has had material consequences ever since for the alignment of class and race in our country.

It makes me wonder, though, what would happen if we locked JD Vance and Elizabeth Warren in a room and said, “Go, make our country better for everyone.”