Thoughts on the Crisis of Sociology

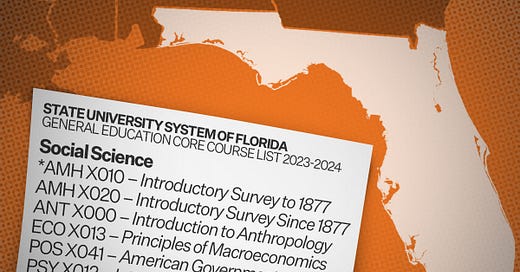

Okay, so I’m a sociologist. You might have seen that the Florida Board of Governors approved regulations that remove sociology from the general education requirements at state universities. Although sociology courses will still be available to students, they will no longer be required as part of the core curriculum. The board's decision was influenced by the perceived need for a change in educational focus, specifically towards “a factual history course” as a replacement focused on “America’s founding, the horrors of slavery, the resulting Civil War, and the Reconstruction era,” whatever the fuck that means.

Alongside curricular changes that removed sociology from the core curriculum, the Florida Board of Governors also approved a regulation that prohibits the use of state or federal funds to support campus activities that advocate for DEI, or “political or social activism.” University student governments are still allowed to fund DEI programs, but only with non-state-granted funds.

Something that you might not have heard about is that a few weeks ago, Springer-Nature Publishing kicked out the entire editorial staff of one of the highest-profile critical sociological theory journals, Theory and Society, and replaced them with a bunch of somewhat random, more science-minded people. The new editorial staff, in conjunction with Nature, published a manifesto for the new vision of the journal that included passages like:

Sociology today is riven with political tribalism and fraught with an absence of vision for understanding the operation of the socio-cultural universe…As a discipline, a monoculture of critical approaches utterly dominates, and, though often well-intentioned, this monoculture is undermining sociology’s professional legitimacy. Similar problems exist in sociological analysis around the world. This is an unacceptable state of affairs and calls for a theory journal devoted to scientific sociological theorizing.

There was an uproar from the crew of high-profile critical theorists that had control over the journal and, admittedly, were dutifully carrying out the journal’s original somewhat critical vision. Ultimately, this was more of an instance of corporate tyranny than an anti-woke coup. The journal will get worse.

It seems that right now, sociology wants it both ways: to be a critical field and a scientific one at the same time. Now, I should say, I don’t think this is impossible. I actually think that this is what drew me to sociology in the first place—that it seemed like a home for a huge range of approaches to knowledge-making all focused on the messy world of human societies. Honestly, most other fields are boring as fuck.

And yet, this past year, the announced theme for the 2024 American Sociological Association Annual Meeting (ASA) was “Sociology as a form of liberatory praxis: an effort to not only understand structural inequities but to intervene in socio-political struggles.” On one hand, great, but on the other hand, its hard to get away with pitching the field as one of disinterested scientists just studying society.

In fact, when Florida pulled their shit, ASA released a statement saying that “the decision seems to be coming not from an informed perspective but rather from a gross misunderstanding of sociology as an illegitimate discipline driven by ‘radical’ and ‘woke’ ideology. To the contrary, sociology is the scientific study of social life, social change, and the social causes and consequences of human behavior.” There is an obvious tension here: sociology as an intervention in liberation versus sociology as a legitimate scientific field of study.

Now, there are a million interesting conversations that this tension could and should precipitate, but I want to hone in on just one in an admittedly very sociological way: there is a difference between individual sociologists and the institution of sociology.

This might be surprising, but I am actually sympathetic to the idea that the field of sociology has become too critical. I do not think that it benefits anyone—including the marginalized communities that some sociologists, through their personal praxis, are aimed at liberating—for ASA to formally orient an entire annual event around sociology's explicit intervention in political struggle. Not only does it confirm a public misunderstanding of the field as overly “woke” and unscientific, but it also, I think, does a disservice to the complicated project of stitching together a uniquely diverse field of study within which there are some of the most rigorous and foreward-thinking scientists in any field today. In other words, it has both internal and external community effects on the field.

Now, I am also one who thinks that sociologists should be at the forefront of putting legitimate scientific knowledge about society into the public sphere. Sure, maybe I want it both ways too. But, here, we really do need to separate—as best we can, and we cannot fully—the scientist from the field itself. While Boomer social scientists deny the role of individual subjectivity in their science, Millennial social scientists, drunk on Foucault, Latour, and a million other French postmodern philosophers, deny the role of collective objectivity in their “science.” These same people might critique scientific objectivity as an inherently racist and colonial construct, which is a fun thing to say but also totally misunderstands the “liberatory” political flux of the Enlightenment, the scale of widespread liberation it has cast, and the North American indigenous origins of the ideas themselves. But, to bring this back, I’m still not sure that the field of sociology and its institutions should be at the forefront of political matters.

Now, one might say you can’t separate sociology from sociologists. If you say that, I basically just think you’re wrong, and I would urge you to go read some sociological literature, because the irresolvable tension therein is actually exactly what the field of sociology studies.

The truth is that scientific fields like sociology run the risk of delegitimacy and destruction if they fall too far into either pure performance of knowledge: total subjectification or total objectification. There are institutional barriers like peer review and hiring practices that prevent individual sociologists themselves from straying too far in either direction, but there are really few mediating forces for the field itself. And the ones that do exist—for-profit publishers and society itself—seem to be in active revolt.

What is not arguable here is that sociology is in crisis. I am not someone in power in the field of sociology, but if I were, I would be taking these signals seriously. As an old mentor of mine said about feedback, we need to understand that when the world is giving us feedback, we need to treat it like unwrapping a present on Christmas morning. It is not something that the world owes us, its a gift.