What does it mean to be moral? Has it changed over time?

I stitched together decade models from the HistWords: Word Embeddings for Historical Text to see how the meaning of “moral” has changed each decade since 1800.

Word embeddings are vector representations of words in a continuous, high-dimensional space (in this case, 300 dimensions) where semantic similarity is encoded as geometric proximity based on patterns of word co-occurrence in large text corpora. They’re what is behind ChatGPT and other LLMs.

But unlike GPT, which is trained on vast amounts of general internet text, this model is trained specifically on the Corpus of Historical American English (COHA) — the largest structured corpus of historical English, created by Mark Davies. COHA contains over 475 million words from the 1820s to the 2010s, offering a balanced, genre-based view of language change over nearly two centuries.

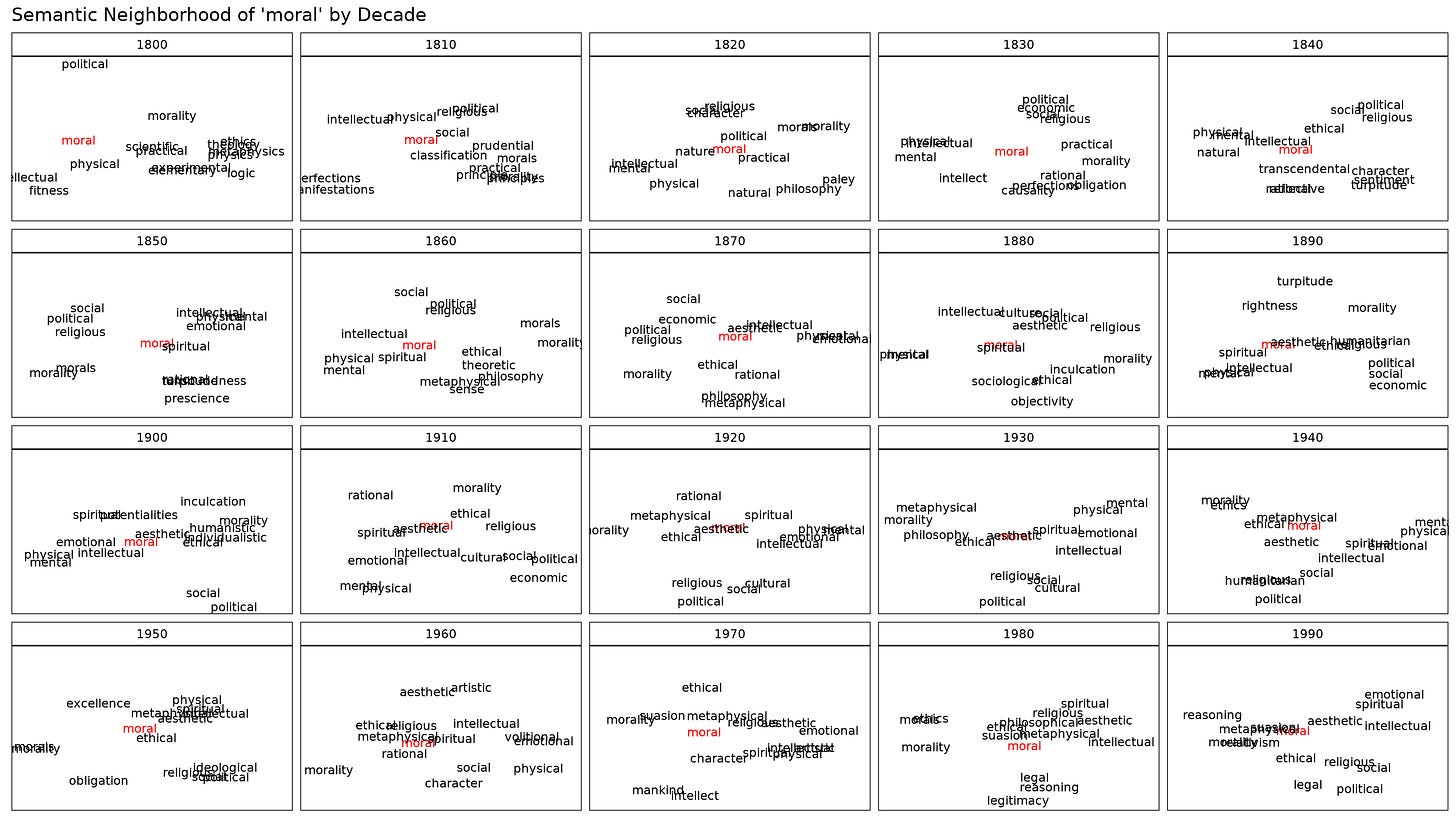

Anyway, here are the words that share the most similarity to the term “moral” each decade since 1800:

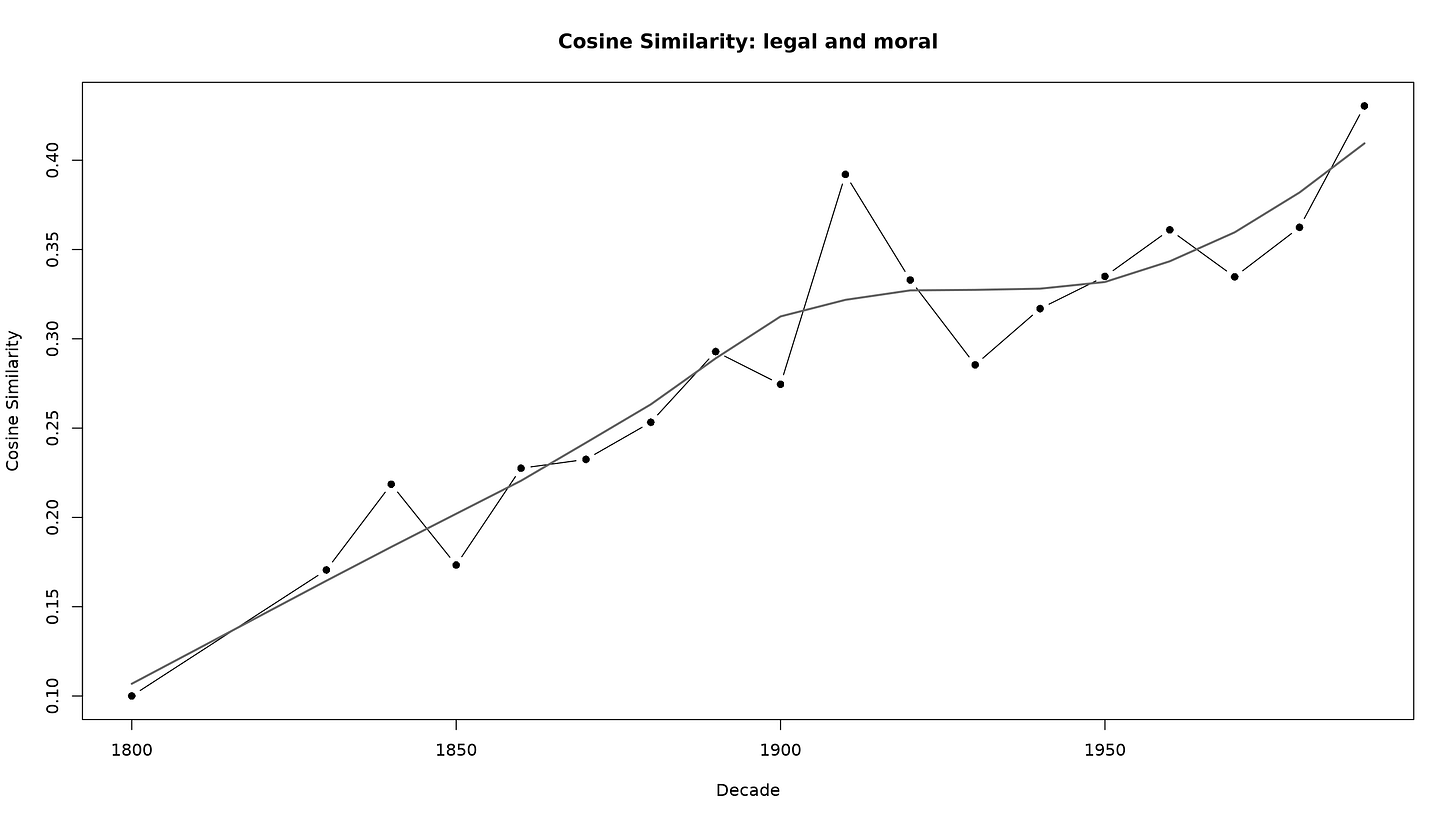

These kinds of charts are fun to look at. It’s like a “Where’s Waldo” of the humanities. Do you have any theories? Any hypotheses? Here’s one of mine: moral reason has become more legalistic. So, let’s test that. Below is the chart of the semantic similarity between “moral” and “legal” over the past 200 years:

Damn. Max Weber was right! We’ve fully bureaucratized our world and been subsumed by the giant national mechanism.

The Puritan wanted to work in a calling; we are forced to do so. For when asceticism was carried out of monastic cells into everyday life... it helped to build the tremendous cosmos of the modern economic order. This order is now bound to the technical and economic conditions of machine production... with irresistible force. Today the spirit of religious asceticism... has escaped from the cage. But victorious capitalism... no longer needs this support. The rosy blush of its laughing heir, the Enlightenment, seems also to be fading, and the idea of duty in one's calling prowls about in our lives like the ghost of dead religious beliefs.

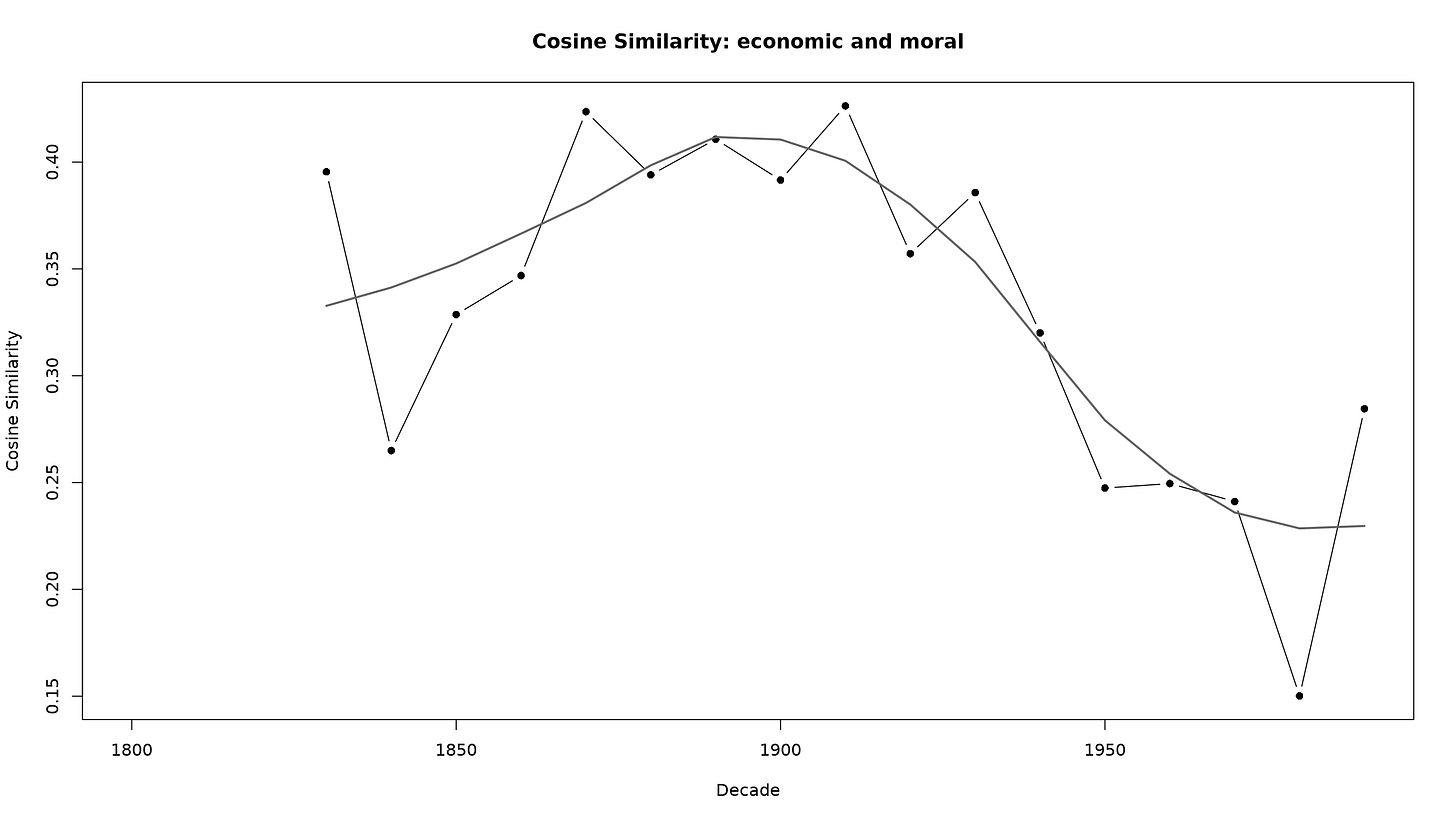

But if Weber is fully right, the meaning of morality must also be turning toward the economic. What is economic is what is moral, right?

Not so fast! What we see is a kind of convergence around 1900 between the two concepts. This was a moment when economic life was morally contested. Many modern nations, even in Europe, were coming into being. Were they to be socialistic or capitalistic? After this period the decline reflects a modern split between technical-economic reasoning and ethical evaluation—a key concern for thinkers from Weber to Polanyi.

In other words, economic thought became plain reality. Economic reasoning was no longer a part of moral discourse because, well, it was superior to it.

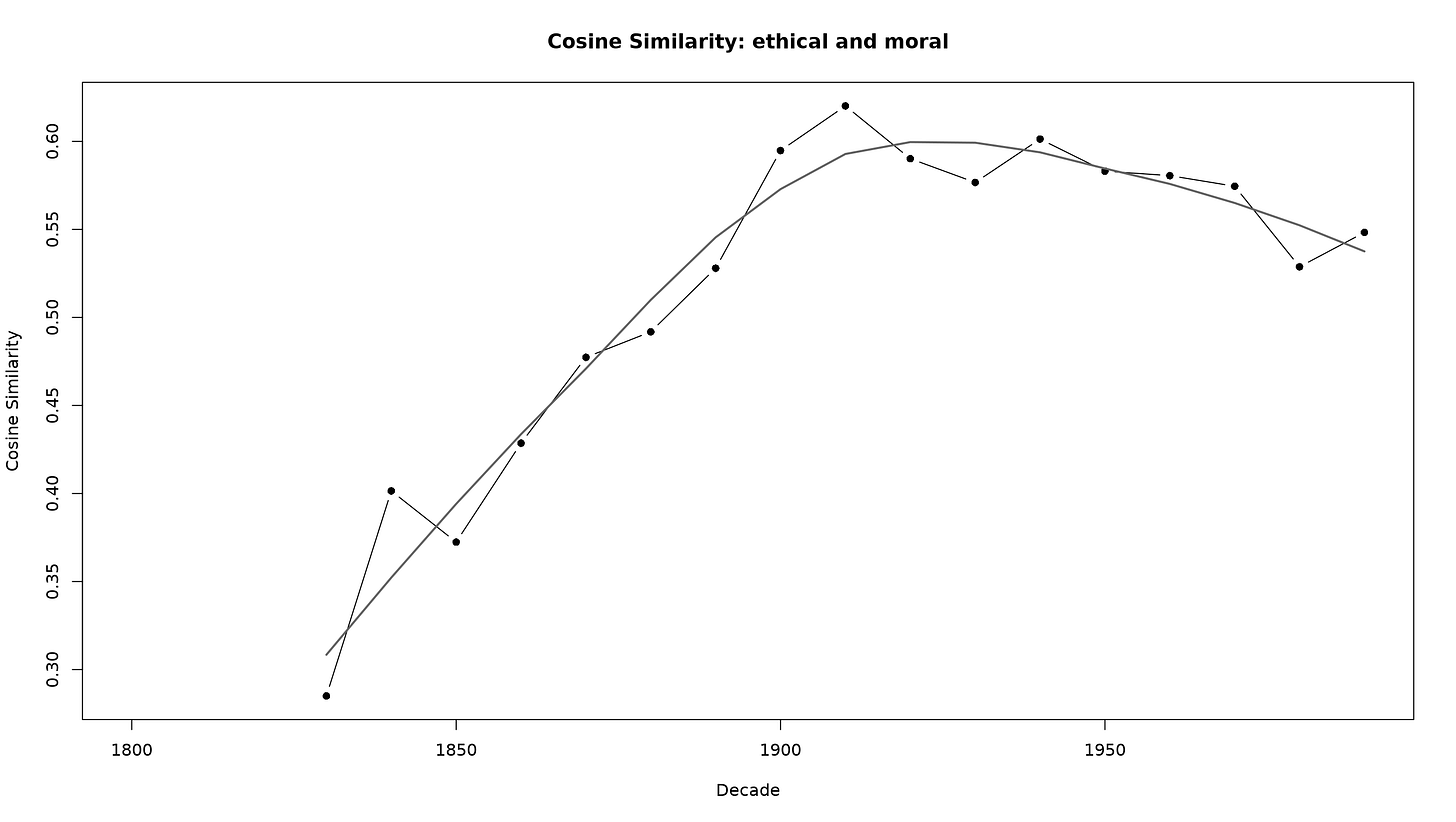

Amongst this split, the sort of soft, dumb, marginalized, sentimental idea of ethics saw a rise. Today most of us think about moral and ethical judgments being the same thing, but they were not until quite recently, and we can see this below. As we approach 1900, moral and ethical discourses converge and then stay relatively linked ever since:

Again, although we think of them as the same thing today, morality and ethics are not the same thing. While morality is about what people believe or feel is right, ethics is about how we reason about what is right. Put differently: morals are lived; ethics are thought.

Which makes sense. If after 1900 the world slowly became subsumed by rationalism and bureaucracy, then we might find ourselves thinking more about what’s right based on this shared plane of modern rationalism than talking about what we, our messy, fucked-up animal with dumb opinions and needs and desires, feel is right.

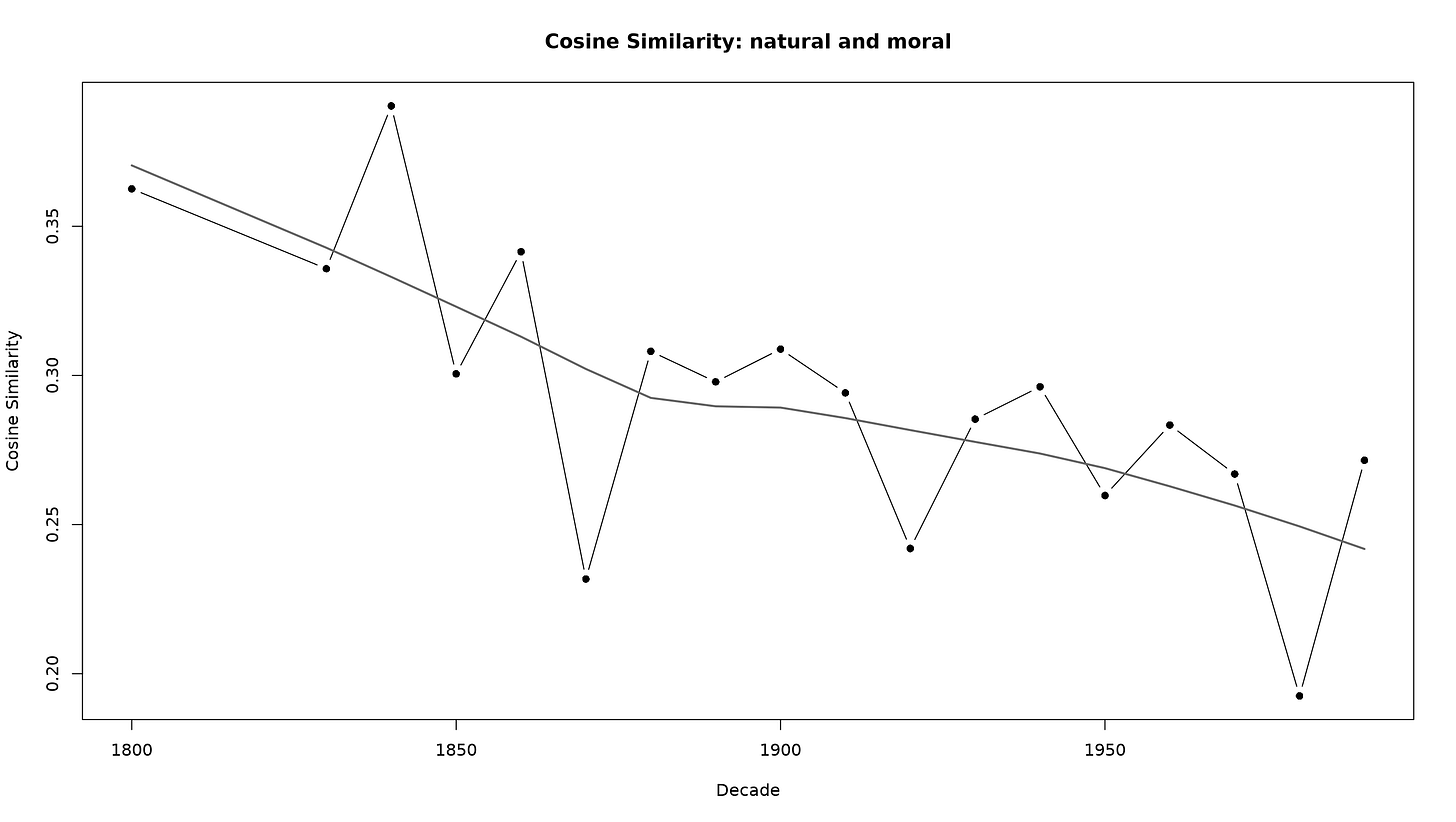

If this is right, we might come to hypothesize that there is a chance that what is natural and what is moral have become unlinked. As we are subsumed by society, by what Norbert Elias called “the civilizing process,” we lose some part of our lived animal. As we replace feelings with thought, society grows. We look upon what we feel is right with skepticism and concern ourselves with what we think is right.

There are a lot of caveats to a method like this. But nonetheless, these models are fun to play with. We can learn a lot about what is often referred to as longue durée or processual sociology, or the endurance and flux of people, groups, and ideas over time.

If you have other hypotheses or questions about the changes in our language since 1800—not just about morality—drop them in the comments, and I can put up a new graph down there!

I wanna know if there is a relationship with talking about morals and talking about political ideology, like it ppl get their morals from their politics more. But idk what word you’d use for it

And also I wanna know if one’s morals are associated with religion less. My pet hypothesis is ppl used to get their morals from their religion and now they get it from their politics