“They’re poisoning the blood of our country. That’s what they’ve done.”

When Donald Trump says this kind of thing about immigrants to the United States there naturally emerges a market for hot takes drawing parallels to Adolf Hitler’s "blood poisoning" rhetoric in Mein Kampf. And yet, this is only the most explicit version of a much broader shift in the American right’s political imagination—one in which health, rather than justice, security, or economic growth, has become a dominant framework for understanding social and political crises.

Around the same time as Trump’s “poisoning the blood” comments, Robert F. Kennedy Jr. claimed that “Pesticides, food additives, pharmaceutical drugs, and toxic wastes permeate every cell in our bodies…We are mass poisoning all of our children and all of our adults," Marjorie Taylor Greene demanded that the government "Stop spraying stuff in our skies," and J.D. Vance was talking about getting radically liberal ideas “out of our schools or it’s going to poison the minds of our young people.”

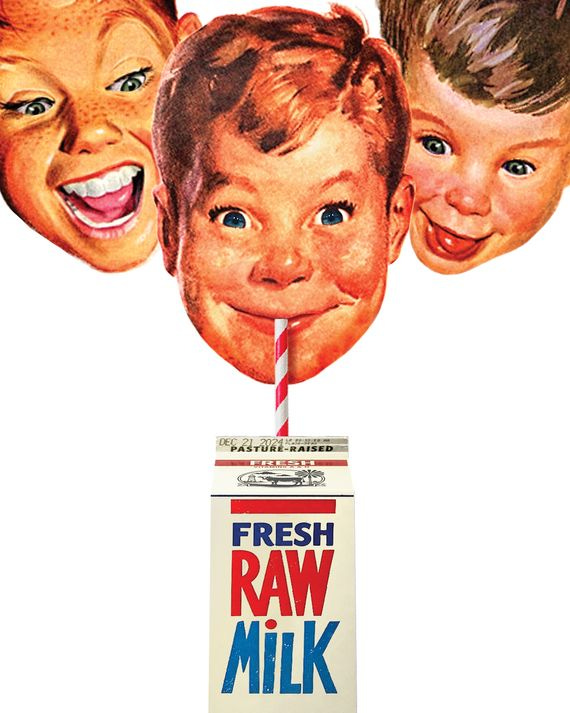

In the minds of many on the American right, we are living in an era of toxicity, where unseen chemical and ideological forces are corroding the vital Anglo-Capitalist force of the American body politic from within. Health, more than security or prosperity, has become a central political virtue. The right’s vision of the past is not just one of economic might or moral clarity, but of the cleaner times of the 1950s when women were in their asbestos-insulated kitchen and kids got sprayed with DDT as they walked home from a more Bible-forward public school.

Today, however, the poisons are everywhere—in our food, in our water, in our bloodstream, in our culture. The American body is sick, and someone is to blame. From plastic particles to gender ideology, from seed oils to migrant caravans, from the mRNA vaccine to the fourth-wave feminist—society is not just in decline, it is in a biological crisis. And like any biological crisis, the only acceptable response is removal, detox, and purification.

While health has long been valued as a societal virtue, the political narratives and metaphors it reinforces today are fundamentally different from the humanistic ideals of the 20th century, such as prosperity, security, and justice. When health is a societal virtue, the nation becomes a body—a cohesive, interdependent whole that might get sick. Under this aesthetic regime, our political imagination shifts from one focused on justice and prosperity toward a more timeless authoritarian form.

In Greece, Plato’s Republic was healthy when its organs were functioning in sync—each part (rulers, warriors, workers) must be in alignment for the whole to flourish. In Rome, Cicero famously declared, “Salus populi suprema lex esto”—“The health of the people shall be the highest law.” This wasn’t just a legal maxim; it was a moral and political ideal. Cicero saw the republic as a living entity, its "health" tied to the balance of its parts: the Senate, magistrates, and populace.

When harmony and order become goals, it follows that corruption and disorder become symptoms of societal pathology. Unlike economic malaise or racial injustice, the language of organic political critique is organized around illness. The lines between literal disease—e.g., COVID or the Black Death—and societal “sickness”—e.g., the 2008 Financial Crisis or George Floyd protests—become fuzzy. In Nazi Germany, for instance, the removal of parasitic and dirty populations of people went hand in hand with state-driven campaigns against tobacco, meat consumption, and cancer.

This fuzzy concept of societal health may seem obvious or insignificant at first glance. However, it is crucial to recognize how these politics differ from the 20th century societal goals of prosperity, security, and justice.

Consider the fact that economic prosperity frequently comes hand-in-hand with all kinds of imbalances, both biologically and sociologically. While early Industrial London roped in enormous trade surpluses, human feces piled up in the streets, coal ash settled in the lungs of every child, and riots became a local pastime. During the Gilded Age in the United States, financial and territorial expansion came hand in hand with monthly labor and race riots. Today, the informational prosperities afforded by the Silicon Age have come along with massive spikes in depression, suicide, and political instability. While monumental in terms of progress and prosperity, none of these periods were harmonious.

The societal virtue of prosperity is about growth and accumulation—not sustainability, but trajectory. From this normative perspective, a good society thrives on expansion, not equilibrium. It doesn’t need harmony so much as momentum. Like a mountaineer sacrificing two frostbitten fingers for the glory of the summit, a society might be riddled with inequality and unrest and yet seen as good if the balance sheets show a surplus. Where health asks, "Are we whole?" prosperity asks, "Are we gaining?"

A healthy society is a balanced whole.

Or, consider the fact that a healthy society is not necessarily a just one. For instance, according to the Southern Antebellum preacher James Henley Thornwell, slave plantations were generally beacons of “healthy” and balanced societies, "like the vigor of a healthful body, in which all the limbs and organs perform their appropriate functions.” A well-run plantation might be harmonious, sure, but in what form, and at what cost?

A just society meets a set of external criteria—whether religious like the Ten Commandments or secular like the U.S. Constitution. A healthy one, however, is more elusive. A just society is abstract and measurable. A healthy society is visceral—society can be "just" yet frail, like a legally fair but economically broken state. Health doesn’t require abstract criteria; it’s felt and immediate, not something to be measured, but something that feels ‘right.’ More often than not, the associated feeling of an unhealthy society is that of disgust or violation—not fear or righteousness.

A healthy society is sensible and felt, not measured.

Finally, while security may be a requirement for a healthy society, the two are not the same. Whereas the politics of security implies an external Other, health implies an internal one. Security is concerned with survival, health is concerned with harmony.

Although they often get lumped into one debate, “securing the Southern border” and mass deportation are, in many ways, two separate issues. While the former is an issue of national security, the latter is one of national health. For instance, while there might be an assault on our Southern border, those who are already here are the ones “poisoning the blood of our country.” These are two totally different sets of political problems with entirely different sets of policy solutions.

An unhealthy society is threatened by an internal imbalance, not an external Other.

This is the messy backdrop against which we must understand the unholy alliance between the American right-wing and the health-obsessed followers of Robert F. Kennedy Jr. that now comes under the banner of MAHA (“Make America Healthy Again”). In this milieu, the personal and the political are nearly indistinguishable. As the proto-New Age Emerson said in 1886, “[e]ach new fact in his private experience flashes a light on what great bodies of men have done, and the crises of his life refer to national crises…the fact narrated must correspond to something in me to be credible and intelligible.” Remove the poisons, and health will return.

Today, the politics of health are, for better and for worse, proliferating on the American right. For instance, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recently banned the demonstrably cancerous use of Red Dye No. 3 in foods. This substance has been banned in Europe since 1994. Great. Remove the poisons, and health will return.

Since the beginning of the year, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) has deported over 37,000 illegal immigrants from the United States. Remove the poisons, and health will return. Well, sort of. By this time in his presidency, Biden had deported more than 57,000 and yet this fact was not narrated such that it linked personal and national crises.

A quick pivot to the spectacular—Trump’s wheelhouse—has led to the arrest and likely deportation of the Columbia University graduate student Mahmoud Khalil in a string of what has been promised as "the first of many [deportations] to come" of “Hamas supporters in America.” Remove the poisons, and health will return.

The point here is not about the details of any of these particular cases, but rather that the attentional value of this motivational political frame has skyrocketed. It is a politics that finds power and virality in a feeling of disgust (“They’re eating the cats!”). The politics of health feeds on paranoia and shits out hypochondria (“Democrats are, to me, the enemy from within”).

Somewhere in this milieu, “self-help” and “America First” become one theory. A top wellness podcast right now, “Culture Apothecary,” hosted by right-wing commentator Alex Clark is not just about Red Dye No. 3 and 5G regulation, but a space for “raw, unpasteurized truths” where “each guest provides their own remedy to heal a sick culture.”

If the social justice era was permeated by demands for the recognition and reparation of historical injustice, today’s health era is permeated by recurring demands for the rooting out of poisonous materials, actors, and ideas that are sickening us all. My guess is that this is not what second-wave feminists envisioned when they popularized the phrase, “the personal is the political.” Or maybe that is exactly what they meant.

The truth is that while this health politics is proliferating on the American right, it is indeed a politics that has left-wing manifestations too. Consider the title of the

The Ezra Klein Show from today, March 14:For me at least, there actually is a distinct sense of hypochondria in the way some N95-clad white Americans go to great lengths to emphasize that the United States is an irredeemably racist project at rallies. While the realities of structural oppression might be true, the politics that have flown from this fact in recent years feel more akin to health than justice.

Just as the right frames national decline as a biological crisis requiring purification, some on the left approach America’s racist history as an ineradicable infection that shows symptoms even in the smallest microaggressions. Given its metastatic nature, this illness is so deep that the only appropriate response is relentless monitoring and self-policing. In this overly sociologized universe, even the smallest crises of personal life refer to national crises.

The rise of health as an aesthetic politics signals a shift away from deliberative, justice-oriented politics toward something more primal and instinctive. When a society sees itself as sick rather than unjust, the goal is not negotiation or reform but purification and expulsion. This shift in discourse also signals a more simple shift toward internal domestic issues that transcends ideology. Health politics is powerful because it's felt rather than reasoned, visceral rather than debatable. And in a time of heightened uncertainty, when the world itself seems poisoned by crisis, the politics of health offers the simplest promise of all: remove the toxins, and everything will be made whole again.

If you made it this far, PLEASE “LIKE” <3 the post up above. It helps a ton with visibilty. And let me know your thoughts with a comment below!